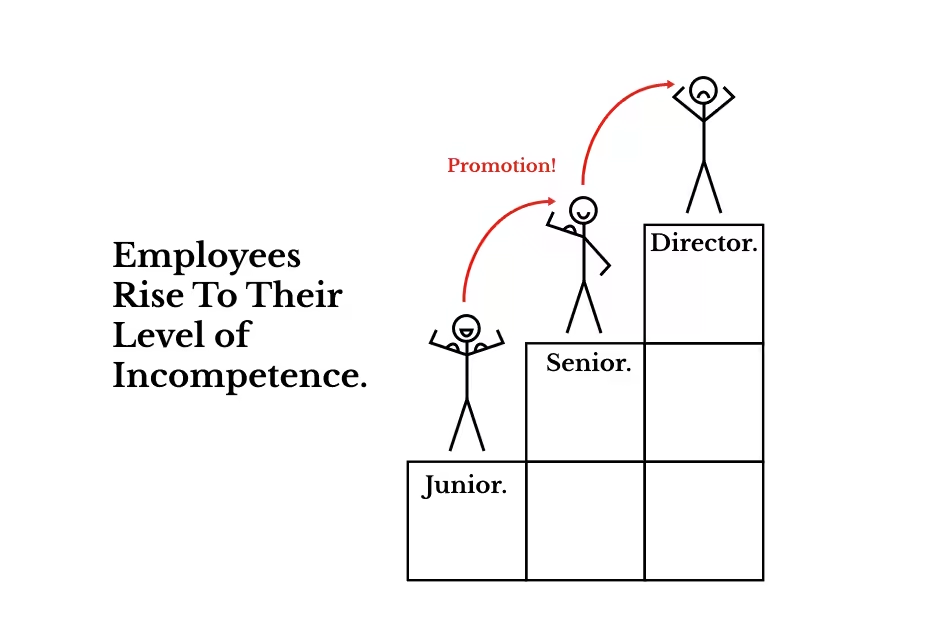

Peter Principle is a phenomenon where every employee tends to advance through the organizational structure until they reach a degree of individual incompetence. Accordingly, the Peter Principle is based on the paradoxical notion that competent employees will continue to be promoted and will, at some point, reach positions for which they are incompetent. They will then remain in those positions because they do not exhibit any further competence that would make them eligible for additional promotion.

The theory was developed and named by Dr. Laurence J. Peter, a German psychologist and philosopher, in the 1970s. Dr Peter observed that in hierarchies such as the military, regardless of how well a person performed their job, they would frequently be promoted until they reached the rank of General. This occurred because the military required extensive training and experience, so when people were promoted to positions in the military, they appeared to be good candidates for advancement. However, they could not perform in their new position because they were promoted to a position that required different skills than those required in the old position. They would eventually be in the position of greatest incompetence.

According to Peter Principle, advancement is a reward for competence because competence is obvious and thus always noticed. After the individual attains a position where they are unqualified, they will be examined by their input more than their output. This means input factors such as arriving on time and maintaining a positive attitude would be critiqued more than performance.

Dr. Peter argued that employees are more likely to stay in jobs where they are incompetent because incompetence is not grounds for dismissal. In other cases, where incompetence is severe, the employee is fired. Eventually, every position in a particular hierarchy will be filled by employees who cannot perform their respective positions' duties.

Dr. Peter proposed a possible solution to Peter Principle phenomenon in which companies would provide specific, adequate skill training for employees receiving a promotion.

How it works (Performance, promotion & Peter Principle)

Peter Principle is prevalent in situations where people downplay the aptitude for management when making promotion decisions in organizations. In most cases, promotion decisions are made largely dependent on current performance. Therefore those who excel in their current roles are promoted to managers despite not having the necessary management skills.

Economic literature shows that some organizations make a trade-off between the Peter Principle and the motivation of employees. Despite rising to their highest level of incompetency, most employees are motivated by knowing that their efforts can be recognized through promotion. The suboptimal matching to managerial positions may be the price organizations pay to incentivize worker effort.

Promotion is key for the Peter Principle to manifest. Promotions serve two purposes in organizations. First, they place employees in positions where they can have the biggest impact on the effectiveness of the company. A second function of promotions is to give incentives to lower-level employees who value the money and prestige that come with rising in the company hierarchy. Likewise, Peter and Hull (1969) argued that promoting a productive employee "serves as a carrot-on-a-stick to many other employees." Therefore, when one productive employee is promoted to a managerial position, other ambitious employees will likely work harder to receive recognition. This improves the overall productivity of an organization.

The available literature has identified at least four factors that may influence a firm's decision to adopt promotion-based incentives (in addition to other forms of remuneration). Firstly, because managerial positions provide status and are easily marketed on résumés, workers may value them as a prerequisite for promotion.

Secondly, incentives based on promotion also lessen the potential negative spillovers brought on by extreme horizontal pay disparities. Vertical pay inequality (as would be linked with promotion-based incentives) can stimulate effort. However, according to research by Cullen and Perez-Truglia (2018), horizontal pay inequity can demotivate worker effort. Similarly, Larkin, Pierce, and Gino (2012) contend that high-performance compensation has psychological repercussions that affect the entire organization.

Third, organizations may commit to promoting employees based on objective performance measures to avoid perceptions of inconsistency, influence activities (Milgrom 1988), and favouritism (Prendergast and Topel 1996; Fisman et al. 2017), all of which could make cash compensation more expensive than promotions. According to a specific argument for the Peter Principle by Fairburn and Malcomson (2001), businesses require senior managers to elevate productive employees since monetary incentives are more likely to sway behaviour.

Lastly, policies for promotions based on verifiable success data, like sales, may deter the manipulation of other, more fungible performance criteria, such as credit sharing and collaborative experience (DeVaro and Gürtler 2015; Fisman and Wang 2017).

It is critical to note that not all promotional processes lead to the Peter Principle but only where managerial aptitude is not considered. However, some organizations still prioritize current performance over managerial aptitude due to a culture of promotion-based incentives. Therefore, in such cases, the evidence of the Peter Principle does not indicate organizational errors but an expensive trade-off between promoting the best future managers and motivating employees.

Evidence of Peter Principle

Understanding Peter Principle is critical because it explains why a company behaves the way it does in terms of performance. Although models can be developed to predict its occurrence, practical, real-world evidence is difficult to obtain. Economists Alan Benson, Danielle Li, and Kelly Shue researched to put the Peter Principle to the test. Between 2005 and 2011, they performed a study with 53,035 sales employees from 214 American companies. They analyzed the data they collected in 2018 to determine performance and sales practices. During that time, 1,531 sales reps were promoted to sales managers. They discovered companies were likelier to promote employees to managerial positions based on their previous performance. This was done without regard for their ability to perform well in the higher position.

According to the researchers, high-performing sales employees were likelier to be promoted, consistent with Peter Principle. The same employees were more likely to perform poorly as managers as well. Their incompetence resulted in significant costs to the company.

The researchers observed that, even though organizations are more likely to do the latter, the best worker is not always the best candidate for a managerial role. The performance of subordinates suffers when the position is filled by someone who previously worked as a salesperson. Their study also realized that companies that rely more on sales as a promotion measure stand to pay double for that mistake. Removing a high-performing sales associate from the line may risk their client relationships, negatively impacting those accounts. Drs. Benson, Li, and Shue observed how frequently most businesses find themselves entangled in Peter Principle and how frequently they knowingly live by it.

Again, according to Daniel Pink's research, people who are promoted to positions requiring different skills perform poorly. The study found that the worst managers are those who often get promoted to jobs unrelated to their current ones. In contrast, the best managers are promoted to positions similar to their current roles. This is because the new position requires skills they already possess, which results in higher performance.

Peter Principle and criticism

Peter Principle arguments are varied, and there has been criticism as well. It has been argued that the Peter Principle is broadly applicable to contexts where success at one level of an organizational hierarchy may need different abilities than success at the next level. This includes science, engineering, manufacturing, academics, or entrepreneurship. Grabner and Moers (2013) researched how performance indicators are picked for hiring and promotion decisions to prove this. They used comprehensive promotion data from a retail bank. They examined how managers use performance metrics for various job assignments. This finding essentially confirmed the hypothesis that mastering the current job does not necessarily translate into mastering the next as tasks increasingly change between hierarchical levels. This reduces the predictive value of current job performance and places more emphasis on subjective evaluations.

Peter Principle has also been referred to as an illusion. The complexity and difficulty of duties increase with organizational hierarchy, so it is normal and common for some employees to experience difficulties. This being true does not prove any systematic errors in the promotion process.

Again, Alessandro Pluchino, Andrea Rapisarda and Cesare Garofalo argued that the Peter Principle implies no correlation between performance at the current level and that at the next level. In turn, they have ridiculed that aspect of the Peter Principle by suggesting that if that is the case, the greatest technique is to promote the worst employees. While it is unknown if they will make effective managers, at least they will no longer be inefficient employees. However, that would lead to a system that rewards failure with promotion leading to the ultimate failure of an organization.

Another Peter Principle critique has argued that it is based on two false assumptions. Firstly, it assumes that if a person is incapable of performing effectively in one job, they cannot do so in any other. The second supposition holds that the person cannot fail, learn from it, and succeed again. Both presumptions are false and show poor management of human resources. Ultimately these two assumptions that underpin the Peter Principle would not be the right perspective for creating and maintaining a collaborative and healthy work atmosphere.

Is Peter Principle relevant today?

The Peter Principle was put forward when businesses were mostly local, and competition was minimal. Individual careers were mostly stable, linear, and confined to a single company. Despite changes in the workplace environment, Peter Principle remains as relevant as ever. As a result, it is critical to consider the various reasons for its current relevance.

Almost 50 years after Dr. Peter developed it, Peter Principle still haunts and terrifies many, if not most, organizations. It is a genuine ticking time bomb that impacts organizations' productivity, profitability, talent management, and customer satisfaction, to name a few.

According to statistics, approximately 25% of newly promoted employees return to their previous positions or leave within a year. 75% of newly promoted employees remain in their new positions but struggle to succeed. They are primarily motivated by the belief that they cannot lead a team.

The 2014 Management & Leadership Study of the world's top corporations by The Gallup Organization found that 82% of the time, employees were hired or promoted due to their technical proficiency rather than their capacity to manage people. Their report was also consistent with Dr Peter's suggestion of the importance of training in organizations. They highlighted that another two in 10 workers exhibit some characteristics of fundamental managerial skills. They can perform at a high level if their organization invests in coaching and developmental programs.

Research has also shown that most frequently in today's work environment, the Peter Principle is observed in technical fields. In these fields, qualified workers are frequently elevated to management positions. Although management capacity determines leadership competence, the technical brilliance of these employees is commonly used in promotional decisions, nonetheless.

Related: The Peter Principle and why it matters to every organisation

Consequences of Peter Principle

Less effective leadership

Although not everyone promoted ends up in a supervisory position, businesses that are susceptible to the Peter Principle may be selecting high-achievers from the ranks for management or executive positions in the long run. Dr Peter's ideas suggest that this may result in less effective leadership, with managers, directors, and others unable to choose what is best for their teams and departments.

Decision making

The decision-making process inside an organization is dependent on people in significant roles. The Peter Principle suggests that some of those decision-makers are unqualified, which results in a portion of the organization's decisions being poor.

Trickle-down effect

Weak leadership has a cascading impact that can result in decreased productivity and lost revenue as procedures, departments, and individuals cannot operate at their highest level. People may be inadvertently plucked from lower ranks as those in positions of authority advance due to the Peter Principle's trickle-down effect. With time, individuals unable to perform their duties effectively may eventually fill many layers in an organization.

Greater potential for error

The overall error rate might rise when roles are filled with individuals who lack the necessary training or expertise. As a result, there can produce defective goods, bad customer service, and significant financial losses.

Poor employee morale

One of the Peter Principle's biggest victims is employee morale. Employees may see people being promoted who cannot perform in the role they have been rewarded with. This can cause negativity in the workforce. Sometimes, another employee (or employees) may feel more qualified and wonder why they did not get the position. Even more commonly, someone who steps into a leadership role and cannot perform well in it can negatively impact everyone else's job and work environment.

How to overcome Peter Principle

Dr. Peter did not simply explain Peter Principle but recommended a few solutions to the problem in his book. He recommended implementing a demotion policy that did not carry the stigma of failure. For example, if an employee is promoted to a role and struggles to perform, top management can return them to their original position.

If a manager performs poorly, the subordinates will suffer automatically. There are several methods for reducing the effects of Peter Principle, such as preparing the employee for the promotion ahead of time. It would be extremely beneficial to inform individuals being considered for future promotions and identify their current skill gaps at that time. As the promotion date approaches, they could be coached and mentored. This process allows for a smooth, professional transition into a role. It reduces the possibility of Peter Principle having an ultimate say.

As more people are promoted to higher positions, most strategic positions are handed over to incompetent individuals. For example, a manager promoted to a top executive position may leave their current position to be filled by an incompetent person. This leads to mediocrity throughout the company, resulting in an incompetent top-heavy organization. Promotion based on ability also aids in the reduction of Peter Principle in organizations. It is preferable to avoid promotion if an individual lacks the natural ability to lead and manage effectively.

Furthermore, another solution to Peter Principle would be to pay employees more without necessarily promoting them. Most employees entertain the idea of promotion mostly because of its salary benefits. To avoid Peter Principle, positive reinforcement in the form of pay will ensure better performance and job satisfaction.

Organizations can change how their policies are formulated to combat the Peter Principle. Lazear claims that some businesses base their hiring and promotion strategies on the assumption that productivity will "regress to the mean" after a promotion. Several businesses have implemented "up or out" policies, such as the Cravath System. The Cravath System explains how employees who fail to advance are occasionally let go. It was developed at Cravath, Swaine & Moore law firm. The firm's policy was to hire mostly new law graduates, internally promote those who performed well, and fire those who did not.

Also, the additive increase/multiplicative drop algorithm has been proposed by Brian Christian and Tom Griffiths as a less drastic approach to the Peter Principle than dismissing workers who do not advance. They suggested a dynamic hierarchy in which workers are frequently promoted or delegated to a lower level. This guarantees that any employee promoted to the point of failure is swiftly sent to a position where they are productive. Dr. Peter also advised managers to replace incompetent employees rather than fire them. In other words, a CEO can reassign an incompetent employee to a position with a longer title but fewer responsibilities. This way, the employee will be unaware that they have been demoted from the position to which they would have been promoted.

The most effective way to avoid Peter Principle is to have alert employees. This means working with a team that is aware of the extent of their capabilities and skills. Employees with such personality traits would consider all additional duties within the new role. They should decline if they do not believe they can perform the new duties and tasks.

To overcome Peter Principle, the employee sometimes must outwit the employer. For example, if employees are well aware of their limitations, they will go to any length to avoid being considered for a position in which they would be incompetent. Dr. Peter described the mode as "creative incompetence. "According to the Peter precept, employees are promoted to higher ranks until they reach a point of incompetence. Simply put, the higher your hierarchy ladder, the more likely you are to fail in a new position.

Related: Everything you need to know about the Peter principle

Conclusion

To minimize the impact of peter principle, prepare employees for higher roles before promoting them. That way you reduce the chances that they will fail.