Few tools in performance management divide teams faster than a stack ranker. In one of the clearest real world snapshots, a case study at Pakistan Petroleum Limited found 67% of lower management and 32% of middle management said the forced ranking system did not reflect their actual performance, and nearly two thirds of lower level managers said they were not consulted before ratings were assigned. This guide is deliberately pragmatic. It explains what a stack ranker is, when it can work, and how to implement it responsibly or replace it so you protect collaboration, credibility, and retention.

Understanding Stack Rankers

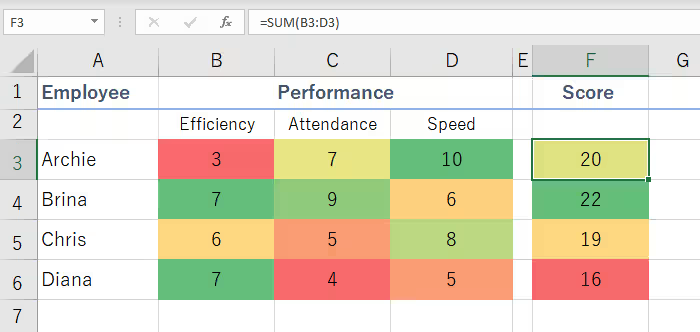

A stack ranker is a performance mechanism that orders employees relative to each other, often into fixed percentage buckets such as top 20%, middle 70%, and bottom 10%. People also call it forced distribution or rank and yank when leaders tie it to removal of the lowest tier. The intent is clear. Differentiate impact, reward the best, and address chronic underperformance. The mechanics typically include manager rankings, calibration sessions among leaders to enforce a distribution curve, and consequences for pay, promotion, and development.

What happens in practice depends on context. A broad, cross study perspective comes from a systematic literature review covering 41 empirical studies across six decades. That review notes differentiation can sometimes spark performance gains, but a more consistent pattern is the perception of injustice. When people believe the process is arbitrary or political, the studies converge on later effects such as damaged morale, counterproductive work behavior, and attrition. The review points to organizational justice theory, which means how fair the process feels to the people affected, as the primary lens people use to judge the system.

Job type also shapes outcomes. In an environment where individual contribution is both discrete and measurable, a stack ranker can model well. A quantitative simulation run over five years in a call center scenario found that removing the bottom 10% each year could drive rapid performance and financial gains, even under typical voluntary turnover assumptions. The logic is simple. When output is standardized, the curve separates signal from noise more reliably.

By contrast, knowledge work and team based settings are where the evidence raises red flags. In a qualitative case study with line managers at a large IT company, the forced distribution element undermined the core purpose of appraisal meetings. Managers described the process as demotivating, uncomfortable, and not suited to development. A practitioner analysis that synthesizes current practice in large tech firms echoes these concerns and quantifies the stakes. Replacing an employee often costs 50% to 200% of annual salary, so a demoralizing stack ranker that amplifies avoidable turnover is economically reckless.

The statistical pitfalls are more than theoretical. The PPL case shows forced curves often collide with reality. Managers there failed to adhere to their own distribution rules. Senior leaders clustered at higher ratings while lower level groups were disproportionately compressed. Small teams fared especially poorly. When you mandate a bottom performer in a high performing five person team, you label a strong contributor as weak by design. That mismatch erodes trust quickly, and trust is the bedrock of any performance system.

Taken together, the literature suggests a narrow window where a stack ranker fits. Transactional roles with clear, comparable metrics, stable definitions of output, and low interdependence among workers. Beyond that, a stack ranker is more likely to suppress collaboration, spawn rating games, and cap recognition for genuine excellence.

Implementing Stack Rankers

If you intend to proceed, start with the evidence and build guardrails to avoid predictable harms.

First, configure the stack ranker with discipline. Define a compact set of job relevant competencies and quantifiable results that matter by role family. Weight outcomes more than effort. The point is impact, not activity. Set clear level descriptors so two managers reading the rubric would place the same person in the same band. Only then consider a distribution. If you apply a curve, constrain it to sufficiently large cohorts, for example a minimum of 20 people in a homogeneous role family. The PPL experience shows that mixing dissimilar roles or small teams with forced curves leads to distortions and grievances.

Second, decide the consequence model. The simulation study’s yank the bottom 10% approach achieved financial gains in a call center scenario, but those dynamics rarely hold in knowledge work. Use the curve primarily to prioritize development, not automatic exits. The cross cultural PPL case underscores how staff interpret intent. Downgrade people to feed a curve, and they view it as politics. Use the distribution to identify who needs coaching, skill building, or reassignment to a better fit role, and the same data becomes a support system rather than a threat. This is where a stack ranker can coexist with a developmental performance philosophy.

Third, communicate the process relentlessly. The literature review’s focus on justice perceptions translates into practical imperatives. Ensure employees understand criteria, how calibration works, and what their rating triggers. In the IT managers’ study, the distribution meeting itself was the source of mistrust. Break that cycle by publishing the rubric, sharing examples of what exceeds looks like in each role, and offering a clear path to improve. Invest in manager capability early. Train leaders to deliver direct, behavior based feedback and to differentiate without hiding behind the curve. Skill building here is not optional. It is the mechanism that turns a stack ranker from a blunt instrument into a disciplined talent review.

Fourth, integrate the stack ranker carefully with pay and promotion. Early on, decouple harsh compensation swings from the first year of rollout. Instead, use a tiered link where top tier outcomes receive visible recognition and opportunities, while mid tier outcomes trigger development plans and targeted coaching. Tie promotion readiness to consistent performance over multiple cycles and evidence of collaboration, not a single ranking event. This approach aligns with insights in practice focused research that urge CHROs to spread feedback across the year and remove bias from ratings before attaching high stakes consequences.

Fifth, monitor and adjust with data. Establish a performance governance rhythm that explicitly checks for four risks the research highlights:

- Distributions that require downgrading high performers to fit a curve.

- Small team distortions and cross role comparisons masquerading as objectivity.

- Collaboration decay, which the broader commentary literature and manager interviews repeatedly flag.

- Avoidable attrition and its cost. Use the turnover cost range cited above to build a business case. Even a modest reduction in regretted exits protects margin.

Complement those checks with pulse questions that target justice perceptions such as My rating reflected my results, I understood how my rating was decided, and I trust the calibration process. If these scores fall, your stack ranker is generating invisible costs that will show up in performance and retention later.

Finally, build alternatives into the operating model. The same practitioner evidence base points to two powerful counterweights. Spread feedback into frequent check ins and tweak rating scales to reduce bias. Make quarterly expectations and feedback cycles the norm, and experiment with rating language and scale design to minimize demographic skews. A stack ranker should never be your only lens on performance.

Advanced Stack Ranker Strategies

Align the stack ranker with culture before you deploy it. The multi decade literature review makes culture’s role explicit. Justice perceptions drive reactions. Run a cultural readiness scan that looks for psychological safety, leader credibility, and comfort with hard conversations. If these are weak, fix them first. Otherwise, the stack ranker will substitute for management and backfire.

Enhance fairness by broadening inputs. In collaborative environments, add structured peer and cross functional feedback, not as a popularity contest but as evidence on specific behaviors that matter such as knowledge sharing, mentoring, and quality of handoffs. This approach reduces the single manager subjectivity that managers in the IT study found so corrosive.

Use analytics to keep the stack ranker honest. Analyze distributions by team size, gender, race, tenure, and role type to surface skew. Create an anomaly dashboard with items such as teams with zero top ratings, teams where the same person lives in the bottom tier for multiple cycles without a development plan, and teams that never use the full scale. Then act. Adjust the rubric, retrain raters, or suspend the curve in pockets where it is harming signal quality. Over time, your stack ranker becomes a data aware calibration tool rather than a rigid quota.

Balance the stack ranker with other talent mechanisms that reward ambition without undermining cooperation. Objectives and Key Results, OKRs, are one option favored by managers in the qualitative IT study because they direct attention to shared, measurable outcomes. Embed OKRs to frame what matters, and use the stack ranker as a secondary view to differentiate contribution within that shared mission. Pair this with succession planning and growth plans so high performers see pathways forward without having to beat peers to escape the middle band.

Be precise about scope. Limit stack ranker use to role families with comparable work and sample sizes large enough to absorb a distribution without absurd outcomes. For small, high performing teams, use absolute standards and narrative assessments instead. The statistical warning in the PPL example, that forced distribution is inappropriate in small groups, is a design constraint you should codify.

Finally, pilot deliberately. If you have transactional units such as service desks, call centers, and certain sales roles, consider a controlled pilot modeled after the call center simulation’s parameters. Use measurable output, annual bottom decile replacement or reassignment, and rigorous onboarding for backfills. Track productivity and financial impact against baseline and include spillover metrics such as team help rates and quality. If the economics work and collaboration holds steady, scale cautiously. If not, shut it down quickly.

Stack Ranker Case Studies

A large technology provider evaluated stack ranking through a teaching case built around Microsoft’s historic model. The problem was familiar. After fast growth, performance lagged peers, and leadership suspected a relaxed appraisal approach. The contemplated solution was a forced distribution to harden accountability. What makes this case valuable is not a final verdict but the trade offs it surfaces. Potential gains, faster removal of chronic underperformers and concentrated rewards for top talent, sit alongside well documented risks. These include internal politics, demoralized meets expectations performers, and collaboration frictions. Subsequent commentary in the broader management literature described how forced ranking inside large tech companies often turned peers into rivals, channeling energy toward optics rather than outcomes. The takeaway for CHROs is clear. The same mechanism that concentrates excellence can also erode the social fabric that sustains innovation.

In the energy sector, the Pakistani exploration and production company highlighted earlier implemented a formal forced distribution. The problem they aimed to solve was inconsistent standards across groups. The implementation introduced a curve and manager driven rankings. The impact, based on employee surveys and HR data, was stark. Most lower level managers felt misrepresented. Many reported that their manager never took them into confidence when assigning ratings. The company failed to adhere to its own distribution rules, with top management disproportionately populating higher bands. Rather than improving clarity and accountability, the stack ranker produced a pervasive sense of unfairness and a visible split between leadership and frontline perceptions. The practical lesson is structural. If your managers do not trust the instrument, or cannot explain it transparently to their teams, the stack ranker will lose legitimacy fast.

A different view comes from a simulated call center environment where the problem was persistent performance variability across a large, uniform workforce. The modeled solution removed the bottom 10% of performers each year and replaced them with new hires, run across both idealized and realistic turnover scenarios for five years. The impact in the model was significant and rapid performance and financial gains. Two insights stand out for leaders. First, the economics hinge on quantifiable, comparable output and a deep hiring pool. Second, the model did not have to overcome the collaboration penalties that plague knowledge work settings. In other words, a stack ranker’s ROI is not a myth, but it is conditional.

Across these cases, one pattern recurs. When work is interdependent and value is created through collaboration, a stack ranker introduces noise and negative externalities. When work is discrete and output is standardized, a stack ranker can function as a blunt but effective optimization lever if you also invest in hiring and onboarding.

A final, current state reminder. Some large firms have used performance management to meet explicit headcount reduction targets. Practitioner reporting has described large scale cuts driven through ratings processes. That may feel expedient, but the visible cost savings often hide replacement costs, loss of institutional knowledge, and chilled collaboration. Treat the stack ranker as a precise tool used in narrow conditions, not an all purpose tool for cost cutting.

A stack ranker is not morally good or bad. It is a design choice. The research record shows that choice must be anchored in context, clarity, and culture to avoid unintended damage.

Performance systems exist to improve business outcomes through people. The strongest studies remind us that perceptions of justice are performance drivers, not soft add ons. If you opt to use a stack ranker, limit it to comparable roles and large cohorts, link it to development before elimination, train managers hard, and build continuous, bias resistant feedback loops. If you cannot do those things credibly today, do not ship the system. Ship manager capability and a transparent goal setting process first.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is a stack ranker?

A stack ranker is a method for ordering employees relative to one another, often into fixed percentage buckets. It is sometimes tied to forced outcomes for the lowest tier and is best suited to roles with comparable, measurable output.

How does a stack ranking system work?

Managers assess results against a rubric, calibrate across teams to enforce a distribution, and apply consequences to pay, promotion, and development. Calibration aims to ensure consistency, but in small teams or mixed roles it can produce arbitrary downgrades.

What are the benefits and drawbacks of using a stack ranker?

Benefits include clearer differentiation and, in transactional environments, measurable performance and financial gains as demonstrated in a five year call center simulation. Drawbacks, documented across decades of studies, include perceived unfairness, gaming, reduced collaboration, and attrition, especially in knowledge work.

Can a stack ranker be used to rate job specific competencies?

Yes, but define competencies by role family, weight outcomes more than effort, and publish level descriptors. This reduces subjectivity and helps employees see how to advance. Avoid cross role comparisons. They feed the perception that the system is political rather than performance based.

How can organizations ensure fairness and transparency when using a stack ranker?

Start with a clear rubric and minimum cohort sizes, communicate how ratings are made, train managers in hard feedback, and monitor justice perceptions through pulse surveys. Add structured peer input for collaborative roles and analyze rating distributions for bias. If fairness signals sag, pause the curve, fix the design, and only then relaunch.