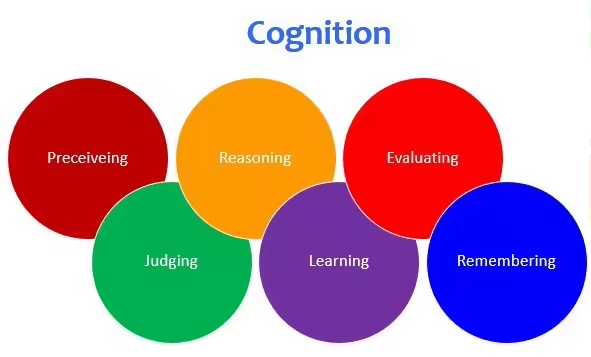

Cognition explains how individuals perceive the world and the actions that come after that. It also refers to “the set of mental abilities or processes that are part of nearly every human action while we are awake.” Subsequently, Gottfredson (1997) defined cognitive ability as “a general mental capability involving reasoning, problem-solving, planning, abstract thinking, complex idea comprehension, and learning from experience.” Therefore, cognitive ability encompasses brain-based skills needed to carry out tasks successfully, that range from the simplest to the most complex ones.

Furthermore, it is critical to note that while they may be interrelated, cognitive ability and intelligence are not interchangeable terms. While intelligence is “ a score that stays relatively static in adulthood, an individual’s cognitive ability can be trained and improved.” Similarly, Cognitive ability is also influenced by the communication and interconnections between various regions of the brain. Likewise, individual differences in cognitive abilities, whereby one may possess high or low cognitive ability, are affected by these interconnections in the brain.

In furtherance of this fact, a recent study conducted by Professor Fiebach and Dr Hilger from the Department of Psychology and Brain Imaging Center of Goethe University showed that individuals who possess high cognitive ability tend to have brains that show more stable communication in their neural networks, than those with lower cognitive abilities. What is more, where cognitive ability is concerned, a range of sophisticated thinking skills inclusive of neurodevelopmental categories such as systematic decision-making, concept acquisition, rule usage, brainstorming, and evaluative thinking are analyzed.

High Cognitive ability

Correspondingly, high cognitive ability refers to increased capability in this range of complex thinking skills. Additionally, other scholars have also restricted the analysis and determinants of high cognitive ability to the capacity to create and implement innovations from various sources. In this regard, examples of historical figures who have been identified to have had high cognitive abilities include Leonardo da Vinci and Michaelangelo.

Such statuses have been awarded to them due to their great innovations. However, the sole use of creativity as a determinant of high cognitive ability has been deemed problematic. This is because personality types significantly affect innovation, whereby it follows that people with a more creative personality normally tend to be more creative. Therefore, according to this reasoning, individuals possess characteristics that predispose them to innovation, becoming a mark of high cognitive ability.

Related: Assessment Writer What to Look For in a Qualified Candidate

Low cognitive ability

On the other end, low cognitive ability “reflects deficits in acquired knowledge and reasoning skills.” Consistent with Professor Fiebach and Dr Hilger’s study on the brain and cognitive ability, unstable neural networks in the brain characterize low cognitive ability. At the same time, instability in the neural networks can be due to traumatic brain injuries, resulting in low cognitive ability, as neuronal networks and regions are compromised. This means that people who have suffered from traumatic brain injuries are likely to alter their cognitive abilities.

Also, just as high cognitive ability is traced back to one’s personality, so can low cognitive ability. In like manner, it has been argued that certain personality traits reduce an individual’s propensity towards innovation. Such personality traits include authoritarianism and being rule-oriented. Therefore, as some individuals may naturally have a high cognitive ability, others may have a low cognitive ability. However, cognitive ability must not be understood as having extreme ends but rather as a continuum, where an individual may be at the midpoint between low and high cognitive ability.

Implications of cognitive ability

Moreover, “cognitive ability is closely associated with educational attainment, occupation, and health outcomes” (Plomin & Von Stumm, 2018). Cognitive ability is regarded as the best job performance predictor (Schmidt and Hunter, 1998). In support of this argument, primary studies and some Meta-analytic reviews establish a link between job performance and cognitive ability in the United States and most European countries (Ispas et al., 2010; Ones et al., 2012).

However, arguably, the predictive validity of cognitive ability in determining performance is dependent on the complexity of a job. Notwithstanding, Borman et al., 2012 still argue that job performance is impacted by cognitive ability, the acquisition of knowledge about the job, whereby individuals with high cognitive abilities are in a better position to acquire the knowledge needed at the highest possible levels.

Conclusively, cognitive ability is popularly used in the work environment to determine one’s possible success in a position. At the same time, different scholars argue for and against various aspects that affect this phenomenon, ranging from genetics, the environment, and other life experiences.

This article was written by Tinotenda Shannon Denhere, a consultant at Industrial Psychology Consultants. She can be contacted at shannon@ipcconsultants.com