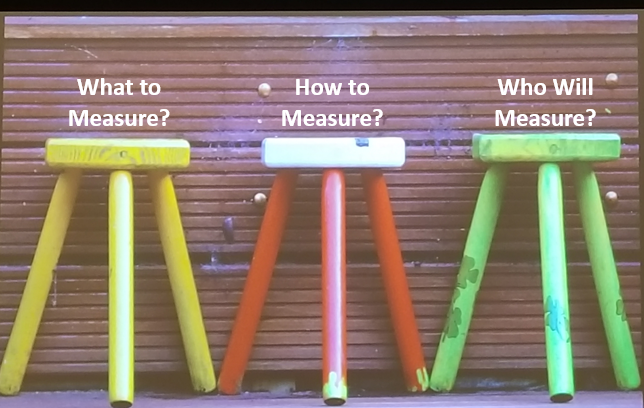

Technological advances, increased connectivity, and globalization are increasing the transition to an economy based on knowledge and information rather than goods. In this changing landscape, human capital is the critical differentiator. Companies need smart, effective employees to compete, so understanding and quantifying human capital is critical for success and future growth. Human capital is concerned with the added value that its people bring to an organization and can be seen as a path for providing an asset link between human resource practices and business performance. Human capital theory, as stated by Ehrenberg and Smith (1997), “conceptualizes workers as embodying a set of skills which can be “rented out” to employers”. The knowledge and skills a worker has – which come from education and training, including the training that experience brings – generate a certain stock of productive capital. Unlike the more tangible forms of capital that depreciate with time, human capital appreciates with time and the cost of added investments is far less than the actual return of those investments. Determining this value is a huge challenge facing the field of human capital. Additionally, identifying how to measure it and who will measure it are also gaps that need to be addressed.

Challenge #1: What will we measure?

The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) in the United States requires extensive disclosure regarding all major assets in a firm including financial and physical assets, as well as technological/intellectual property such as patents. However, they do not require disclosure of what is arguably the largest expense for an organization, their people (Huselid, Becker, & Beatty, 2005). This need to be able to demonstrate the true value of a firm’s workforce is riddled with obstacles. First, there are too many variables to account for when attempting to create an accurate picture demonstrating the true value of human capital, and organizations are tasked with being able to present this value in terms that modern-day finance and accounting professionals can agree with. Secondly, assumptions are made that the investment decisions individuals make will have the same impact for all professions and stages of life (including types of degrees). Lastly, unlike most investments, not all human capital appreciates. All of this makes determining what to measure with regard to human capital very difficult to do.

In addition to being able to measure the value of human capital, organizations need to develop scientific and objective processes to identify and measure important skills and competencies needed to be competitive. They need processes that will help them assess their current state and provide insight into what recruiting, training, and development strategies need to be in place in order to achieve this future state.

The first order of business is to agree on what should be measured.

Challenge #2: How to measure?

Advertisment

As mentioned previously, a challenge facing the field of human capital is finding a consistent method for valuing and reporting human capital on the balance sheet. This will require changes in the accounting profession to value the intangible assets similarly to how research and development costs are currently handled. They are considered as investments and appear as assets on the balance sheet, rather than as expenses on the income sheet.

Cascio and Boudreau (2008) point out that the measurement of HR activities is only valuable if it helps aid in the decision-making process about an organization’s talent and how that talent is organized. This is why it is vital to build a logical framework around the HR measures that are used in the decision-making process. When aligned to these frameworks the measures can be quite powerful. Ensuring that the right data is being captured can only be determined if the logical connections between the measurements tell a “story” (Cascio & Boudreau, 2008). Aside from building a logical framework and the measures themselves, organizations need to be sure the data that is captured is reliable and consistent and that the analysis of the data is correct. Understanding the difference between “causation” and “correlation” is quite vital when interpreting the actual impact of your measures. Lastly, you need to frame the analysis using a mental model that the managers are already familiar with (Cascio & Boudreau, 2008). Building a framework for your measurements will allow for a better understanding of which data is useful and which data is not and bring more value to the measurement, analysis, and ultimately to the validity of the decisions being made about the talent in your organization. Additionally, not all HR measures add value. A firm should focus on the 20 percent of measures that account for 80 percent of the variability in performance (Cascio & Boudreau, 2008).

Relying too heavily on benchmarking data can lead HR in the wrong direction. Benchmarks are averages and oftentimes do not take into consideration the size of the firm, the product focus, location, and corporate culture. Aside from that, every organization is unique because it is made up of human capital that is unique to each firm. Investments by one organization in say, learning, may not have the same impact as it does in another organization. Implementation and communication of a learning program vary from organization to organization and benchmarking data in these cases is like comparing apples to oranges. Additionally, even within one’s own organization, the learning function may operate differently and have a varied impact based on things such as the geographic location or business unit (Cascio & Boudreau, 2008).

As was stated in Deloitte’s 2017 Global Human Capital Trends study, and amplified in their 2018 report, “The Rise of the Social Enterprise”, the organizations that will be able to gain and/or sustain competitive advantage are likely to be those that can “move faster, adapt more quickly, learn more rapidly, and embrace dynamic career demands”1. Deloitte research highlights the need for organizations to recognize the hyper-connected nature of the workplace which will require an even higher level of collaboration and internal integration pushing organizations to think about the way in which networks and teams play a role in achieving their goals.

While it may not be 100% clear exactly how this shift toward a “networked” organization will transform HR processes as we know it, organizations should begin to think about how they will expand their analytics toolsets to include organizational network analysis (ONA). ONA is the application of social network analysis to organizations. Social network analysis uses graph theory and data from surveys and technology-mediated networks (i.e., email) to analyze the structure of and the relationships within a network rather than focusing on the individual attributes of a single employee in isolation. Traditional performance metrics do not do a great job of highlighting the vital role that others may play in an individual’s performance. Social network analysis can help map these dependencies to help organizations gain a better understanding of how work actually gets done.

Challenge #3: Who will measure?

HR should not only be capable of analyzing and interpreting HC Metrics but also recommending and implementing interventions to drive organizational effectiveness. Improved access and utilization of human capital metrics is not a ‘silver bullet’ that will automatically transform HR into trusted business partners but they are enablers for achieving business impact and transforming HR as a function.

As part of the framework of effective decision making in human capital expenditures, an organization needs to be concerned with addressing the logical framework around the measures and assure that the assumptions being made are based on using the right analytics to identify the relevant insights (Cascio & Boudreau, 2008). HR measurement along with the right analytics can also reveal areas in which the efficiency of HR can be improved. It is not just about justifying the investments but also making sure that you are doing the right things for the right reasons.

Improving decision-making effectiveness should be a focus of more than just the HR department. Good HR measures combined with the right analytics and logical framework can help HR play a role in developing and implementing corporate strategy. This also means that HR needs to buckle down and endeavor to understand how decisions made about human capital affect the business and how business decisions made by the business can potentially affect human capital. Both are needed in the strategic management of human capital.

Conclusion

According to Elliott (1991), the human capital theory proposes that “individuals will invest in human capital if the private benefits exceed the costs they incur and that they will invest up to the point at which the marginal return equals the marginal cost”. Experience, education, and the knowledge, skills, and abilities (KSA’s) and employee brings to an organization combined with the multiplicative elements of attitudinal commitment and levels of discretionary effort create value for human capital. Environments that support innovation and creativity are fertile grounds for creating even more potential value with their human capital. Understanding how we can demonstrate and measure this value is a challenge for human capital strategists. Even more importantly, identifying who should be responsible for measuring the value and building the competencies required in order to do so is a challenge that all too many organizations are ignoring. The jury is out as to whether the HR function as it exists today is up to the challenge for playing a strategic role in measurement and analytics. Unless the HR function starts developing their staff to think more critically, requiring more advanced education, and/or selecting employees from functions outside of HR, the HR function will continue to face an uphill battle to be seen as a true strategic partner.

The post \"Human Capital: Three Measurement Challenges Organizations are Faced With Today\" was first published by Steve Hunt here https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/human-capital-three-measurement-challenges-faced-today-moon-phd/

About Michael M. Moon, Ph.D.:

Dr. Michael Moon is an organizational psychologist and former HR practitioner with a Ph.D. in Human Capital Management from Bellevue University. She currently works as the Director of People Insights, part of ADP Professional Services. Dr. Moon has almost 20 years of experience working in HR and HR Technology. Her strong analytical and research skills have enabled the organizations she has worked for and clients she has worked with to do a better job at assessing the effectiveness of their talent choices by helping them to isolate and measure the impact of their human and social capital initiatives. Michael is a highly sought speaker on a range of topics including HR/Talent analytics, organizational culture, turnover, social capital, organizational network analysis, employee engagement, and wellbeing